Kamala And Gopal Singh: Embodying The Progressive Heart Of Hinduism

The mission of Sadhana: Coalition of Progressive Hindus is to build a platform for social justice minded Hindus. Since the founding of Sadhana: Coalition of Progressive Hindus, we have been seeking out people of Hindu faith and upbringing who have devoted themselves to social justice and seva (service) for the most needy and marginalized in our world. We define such people as progressive Hindus. Kamala and Gopal Singh don’t think of themselves as “progressive Hindus,” but they are exactly that — two shining examples of progressive Hinduism.

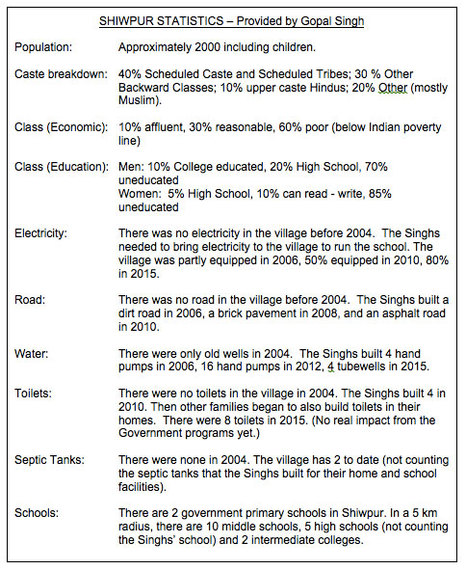

I met Kamala and Gopal a few months ago at their home in Shiwpur, a village some two hours from Varanasi. I was part of a group of pilgrims traveling with Swami Bodhananda, and Gopal and Kamala graciously hosted us for a few days. Together they started the Jangi Singh Girls Intercollege in 2005 — this is a free Hindi-medium school for the girls of Shiwpur Village and some 25 adjacent villages, which Gopal and Kamala run themselves with their own family funds.

Kamala and Gopal live in a large and very comfortable house — it is an old and majestic, renovated with all modern comforts. Next to it are the school buildings, gleaming in their continuously retouched white paint. The house and school buildings are such an anomaly in this traditional, poor village. We walked through the village, and everyone was deferential to the Singhs. I sensed enormous self-respect in the people I met. The lanes were clean, the houses well-kept, and the kids and the cattle seemed well-fed and happy. The Singhs’ driver was also the chief of the village panchayat (governing body), a powerful man! Kamala told me that for the villagers, the job of a driver was very desirable.

Like the best couples, Kamala and Gopal have distinct personalities that contrast and complement (and often, jokingly provoke) each other. Gopal is the quiet one, prone to long evenings reading or discussing politics or philosophy with Swamiji or others in the group. Kamala on the other hand, is a whirlwind, a force of nature. The only time I saw her sit for more than 10 minutes was when I interviewed her. She manages her household and her school expertly, and is constantly solving the life challenges of her staff members, extended family and many village residents. On top of all of that, she and Gopal have an endless stream of guests, and while they are both utterly charming and gracious, it is Kamala that manages guests’ itineraries, meals and all other needs. Gopal watches his wife expend impossible amounts of energy making a miracle a minute happen, and he teases her quietly. Kamala in turn feigns frustration at Gopal for spending so much time talking and reading when there is so much to do. Made for each other, these two. And they’ve been best friends their whole lives.

Gopal and Kamala married when he was 17 and she was just 14. Kamala had been raised by her mother alone since her father had died in her childhood. She had not wanted for anything, and yet her childhood was one of struggle since she wanted very much to be educated, but instead she was married as a child. Once married, she came to live with Gopal’s family in Shiwpur, in the very house where I stayed with them. Kamala talks of Gopal’s father, Jangi Singh, as the most profound influence in her life. He was a man of few words, but he inspired by example. He quietly conducted his own business while helping others each and every chance he could.

Kamala was a big dreamer as a child. Once she was married, her husband and father-in-law both encouraged and loved her, nurturing the dreamer in her. When her father-in-law once saw her crying, he came to her and simply said, “Since you are crying now, you will be happy later on.” Kamala understood that she must accept and go through whatever sadness and challenge presented itself, but that if she did that, happiness would also befall her. And this is how she has lived – accepting, indeed embracing, every challenge. She has also been generous and compassionate throughout her life, just as her father-in-law taught her. Today, Kamala is living the life she always wanted to live – a life of service, right in Shiwpur.

Gopal too talks about his father as his biggest influence. Gopal learned from his father just by watching him — they didn’t have many serious talks about how to live a meaningful life. Gopal never saw his father agitated or excited — he was always patient and helped people as much as he could, whenever he could. Gopal’s father was a follower of Advaita Vedanta, a Hindu philosophy. He was not very ritualistic, although he was not opposed to ritual.

After Gopal completed his engineering studies, he left to make his fortune in the United States. He and Kamala came back quite regularly, and he would be sad to leave his father each time. One time, his father looked at him and said, “Don’t worry. I’ll be here when you comeback.” The next time, his father said the same thing when it was time to say goodbye. But then, there was the last time, when he said, “How long do you want to hang on to me?” Surely enough, Gopal didn’t see his father again.

Jangi Singh’s own inspiration came from Lord Rama. Rama was his hero, although he didn’t worship him; rather, he revered him. He taught Gopal that it was important to emulate Rama in these ways:

* Make yourself capable of distinguishing right from wrong. (viveka buddhi)

* Have the courage to adhere to what is right.

* Have the forbearance to carry out your dharma in the face of all odds.

* Live without regrets.

Kamala and Gopal have learned from Jangi Singh the true happiness of compassionate detachment — they are at peace with all of life, including its challenges, and yet they feel a great responsibility to this world they are living in, and devote their lives to the service of people less privileged than themselves.

Perhaps following Jangi Singh’s example, while they both identify as Hindu, Kamala and Gopal don’t place too much importance in prayer and ritual (bhakti yoga, the path of devotion). Kamala is somewhat more interested in visiting temples than Gopal, but I suspect that this is because she is someone who connects with people, and temples are where most people go. Gopal is more interested in understanding the philosophical underpinnings of Hinduism than Kamala: you could call him a gyana yogi (on the path of knowledge). What Kamala prioritizes above all is doing and giving: she is the consummate karma yogi (on the path of action and service). All of this is done with complete humility and devoid of any self-consciousness. The couple is just living the way they know how, dismissive of any praise they receive.

The village had no temple when Kamala returned in 2004. There was no public space for the entire village to congregate. In spite of their ambivalence when it comes to ritual, Kamala and Gopal built a beautiful Shiva temple for the use of the entire village. The villagers celebrate religious festivals, weddings and other functions there. Gopal explained to me, and I saw with my own eyes, that this temple welcomes all; there is no differentiation made between the different castes.

True to her spirit, Kamala ran an incredibly successful Indian restaurant during many of those years. The restaurant was a labor of love. She brought four chefs from different regions of India so that her guests could taste authentic foods from each region. She paid her staff generously and welcomed her guests each evening in person. She allowed local charities to have their fundraisers there. Needless to say, her restaurant became a popular destination for the people in her community, even though there were hardly any Indians living there.

After some 30 years in America, Gopal’s career became very successful and the family had a surplus of money for the very first time. At first Gopal considered a very comfortable retirement perhaps in Florida where he could golf, read his philosophy and live in peace. But Kamala would not hear of it.

Kamala had known her whole life that there was a larger purpose to her life that had yet to be revealed to her. Throughout her life, she had searched for that larger purpose. Once there was no financial pressure on the family, Kamala knew exactly what she must do: her beloved father-in-law had practiced boundless kindness and charity in Shiwpur Village, and she wanted to continue that work.

In August 2004, without Gopal’s consent, she went back to Shiwpur with the objective of renovating their ancestral home which had fallen into disrepair. She took four men–reputed builders and contractors–with her from Delhi. Once they saw the remote location and the scope of work, they tried to back out. But Kamala is a difficult woman to refuse. What’s more, they realized quickly what a humanitarian she was, and were moved to help her. She built a small hut where she lived for four months while the renovation was taking place. There was no toilet in the village (today several families have toilets) and so she used the fields just like the villagers. In November 2004, when the renovation was well underway and the house was habitable, Gopal joined her.

By then Kamala had taken stock of the most pressing needs of the villagers. She had helped individual families and had started a bi-weekly medical clinic which still runs today. She noted that none of the girls in the village went to school beyond elementary school and announced to Gopal that they needed to build a girls’ school in Shiwpur. They could name it after Jangi Singh.

Gopal, ever the skeptic, researched the situation. He knew there were schools in the vicinity – why couldn’t they encourage the families to send their girls there, and perhaps help with transportation costs? Gopal visited all the nearby schools and was very disheartened. Both the government and private schools were abysmal. The government schools were terribly corrupt, and while children’s names were registered and teachers hired, no actual teaching was taking place. Gopal was convinced that Kamala was right.

People often ask Kamala and Gopal why they built a school just for girls? Didn’t the boys also deserve a quality education?

Gopal had the same questions at the outset but was quickly convinced that a girls’ school was the best thing they could bring to Shiwpur. Most boys did study through high school, but none of the girls did. Gopal repeats the adage, “If you educate a man you educate an individual, but if you educate a woman you educate a family.”

I asked what their father Jangi Singh’s response might be to the idea of a girls’ school named after him. Both Gopal and Kamala smiled, and Gopal told me a story from when they were very young. Because they were married as teenagers, Kamala actually grew from a child to a woman under Gopal’s parents’ care. Gopal’s father would often bring special fruit or sweets for the family, and as per tradition, the male members of the family were served the treats first, and the women and girls got some only if there was any left over. Once, the sweets were eaten by the men, and there was none left. Kamala, still a child, became very upset. And then her father-in-law pulled a last piece from his pocket. She was so dear to him that he had put aside her share first. Contrary to tradition, he had prioritized a girl.

And then Kamala shyly added, “And you know, I wanted to build a girls’ school so that the girls of the village could have the high school education I myself was denied.”

Jangi Singh Girls Inter-College

The school that Kamala and Gopal built is named after Jangi Singh, Gopal’s father and the only father Kamala ever knew.

The school has 550 students, and the capacity for 700. The school is entirely free, and is funded by the Singh family’s own private charity. Kamala and Gopal have poured their retirement funds into this work, and their children have also supported them very generously. Kamala and Gopal set out to serve the girls from the poorest families. They only considered income level when accepting students to the school. Families who had a brick home or owned land were not eligible. Even though they didn’t explicitly set out to serve girls from Dalit and lower caste, as it turns out, 90% of the students are from Dalit and lower caste families, and 10% are Muslim. There are 2 or 3 caste Hindus as well.

There are seventeen teachers: thirteen men and four women. The staff members are all Hindu; four are Dalit.

Gopal and Kamala are trying to bring all the students, staff and teachers together in a way that transcends caste. They have insisted that everyone eat the same food, using the same plates and utensils. Everyone at the school is now used to this openness.

The teachers all play a role in developing the school curriculum, and so they feel great pride and ownership over it. There is emphasis placed on increasing self-esteem and having a vision for one’s life and the world. Courses include self-development, public speaking, and computers. The school has a computer lab with eleven pcs.

I met two teachers at the school, a married couple, Chitra and Bharat Kumar Singh. They have both been teaching almost from the very beginning. Chitra teaches Sociology, Home Science and Art. Bharat Kumar teaches History, Civics and English. They say there is no comparison between this school and other schools in the area. Chitra told me that their marriage has been strengthened because of their work – she and Bharat discuss school matters at home and she finds that Bharat Kumar gives her respect in a way that is unusual among her peers. I asked what the couple’s future plans were, and they both said they wanted to keep improving and strengthening their school. Chitra said that the life trajectory of the girls who attend this school is permanently changed – “Whatever happens in their lives, they have been taught to think independently, and they know they have a responsibility to themselves and the world.”

L to R: Bharat Kumar and Chitra Singh, Gopal and Kamala Singh, and their niece Mausam, in front of the school.

Today, Gopal and Kamala split their time between Shiwpur Village and the United States, where their children and grandchildren live. They spend roughly 9 months (the school year) in Shiwpur and three months (the summer) in the States. The Singhs are in the process of starting a college for the school’s graduates. Families are nervous to send their daughters far to attend college, and the girls want very much to continue their studies. Kamala and Gopal have already built a building next to the school for this college which will offer courses in English and Computer Science. This way, girls have the choice to take computer-related jobs which can be done from home. Kamala and Gopal are trying to partner with a university either in India or abroad so that the college can be properly accredited.

Gopal and Kamala love building their school, and have a wonderful relationship with the parents of their students. They often become aware of problems and crises in families of the students, and do all they can to help. Their relationship with villagers is mostly good, but there is some inevitable resentment because of the sheer boldness of their venture, and because of the obvious economic disparity between them and the village. But Gopal and Kamala do their best to stay focused on their own work and not get affected or sidetracked by these issues. They are conscientious about constantly evaluating and tweaking their programs.

I asked Kamala and Gopal what their long term plans are for the school and college. This question tries their patience. Of course they’d like to think that the quality of their school will be maintained even after them. Of course they’d like the school to be endowed and last a long time. They are hoping that Gopal’s younger brother will become involved in their work, so that he can keep it going when they can no longer. But while these are thoughts that occur frequently to Kamala and Gopal, they don’t dwell on them. Kamala and Gopal find themselves living out the teachings inherited from their beloved father Jangi Singh. They see this work as their dharma, and they are doing it with all their heart, addressing all the challenges that arise without fear and without regrets. In Gopal’s words, “We are doing our best, and building programs and systems to the best of our ability. But if it falls, it falls. We’ll carry on for as long as we can.”

Kamala, of course, has the last word. “For me, it is about this village. I knew I had to serve this village and home which made me who I am. I am doing that now, and will continue as long as I am alive. Just as I came into this house, I will finally leave from this house.”

*****

Building a Progressive Hinduism

Swami Bodhananda wrote these words in response to a draft of this piece: “Kamala and Gopal’s experiment is worth documenting and repeating in every village in India. India has 600,000 villages and America has three million Indian residents who, collectively, can do wonders. Kamala and Gopal Singh are pioneers and I am sure that their work will be stuff of folklore inspiring many others with means, compassion and imagination to follow their path. What I admire in the Singhs is not only their work for the poor and downtrodden, but the philosophy and the spirit of selflessness, joy and perfection that they bring to what ever they do.”

Along with Swami Bodhananda, I implore my fellow Hindus to take Kamala and Gopal’s lead. Speak up for those who face discrimination because of their class, religion, caste, race, sexual orientation or any other reason. Do all you can to address poverty and hunger in the world. And please don’t do your good deeds quietly – join Kamala and Gopal in showing the world what it means to put Hindu values of oneness of all (ekatva), non-violence (ahimsa) and the priority of service (seva), into action.