As India gears up to celebrate yet another ‘Yoga Day’ this weekend, thanks to the hype created by the current regime, yoga has grown into a national style statement. Socialites flaunt yoga couture, new age yoga gurus laugh their way to the bank and workshops, yoga shibirs, retreats and what not hijack the traditional logic behind yoga. Amidst all this hooplah, almost no one remembers the founding fathers of modern yoga, aside from a few students in pockets of the country.

The credit for bringing yoga into the 20th century probably belongs to an unassuming man from a little village in the south. Tirumalai Krishnamacharya could easily be crowned the ‘Father of Modern Yoga’.

Born in 1888 in the remote village of Muchukundapuram in the erstwhile Mysore state, situated in what is now Chitradurga district, Krishnamacharya hailed from a family of scholars and priests. His father Tirumalai Srinivasa Tatachary and mother Ranganayakamma were devout Shri Vaishnavas.

Krishnamacharya was the first of six children. As was the family and community tradition, the young boy’s sacred thread ceremony was performed and his mentoring in the Vedas begun early on. Tatachary passed away when his son was just ten years old, leaving the burden of managing the family to Ranganayakamma.

On the advice of elders, they migrated for greener pastures to Mysore. In Mysore, Krishnamacharya was enrolled into the Chamarajaendra Sanskrit College started by the Maharaja of Mysore. Krishnamacharya studied various schools of philosophy like Nyaya, Tarka and Vedanta.

In 1904, when Krishnamacharya was just sixteen years old, strange things began to happen to him. The legend goes that he had a dream in which he was advised to travel to the town of Alvar Tirunagari in Tamil Nadu. Following that instruction, he traveled to the town, and on arrival there, is said to have passed into a trance.

In his trance, three sages taught him the famous long-lost treatise on yoga, the “Yoga Rahasya”. When he came out of the trance, he was able to recite the entire treatise from memory.

At the age of eighteen Krishnamacharya traveled to Banaras and continued his study in various branches of philosophy – Nyaya, Tarka, Mimamsa, Vaiseshika and so on. He trained under some of the greatest Sanskrit grammarians at the Banaras Hindu University.

For over a decade Krishnamacharya studied these systems of knowledge in Banaras, and traveled further to meet scholars and pundits from Bihar. He mastered what we now know as the Bihar school of Yoga. But this was only the beginning of his journey.

Under the instructions of one of his teachers, Krishnamacharya traveled to Nepal to meet several scholars and gurus. He was advised to learn the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali from one Yogacharya Rammohana Brahmachary who lived somewhere in the Himalayan caves. To travel to that part of the country, he needed the permission of Lord Irwin, the Viceroy of Shimla.

It is said that Lord Irwin suffered from diabetes and Krishnamacharya helped him bring it under control with his yoga therapy. Impressed by his work, Lord Irwin personally made arrangements for Krishnamacharya to reach his destination in the Himalayan caves. It is said to have taken him three months to reach his destination by foot.

Once he reached there, Krishnamacharya spent the next seven years mastering the “Yoga Sutras” of Patanjali as well as rare Tibetan texts of yoga like “Yoga Kuruntha”. He then returned to Banaras.

Sometime around 1925, the Maharaja of Mysore Nalwadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar was visiting Banaras. The fame of Krishnamacharya reached him. He was surprised to hear that a young man from his kingdom was being hailed as one of the greatest scholars of yoga up north. The king promptly invited him back to Mysore.

Krishnamacharya returned to Mysore, married and became the personal yoga guru of the king. The king was a great patron of performing arts like classical music, classical dance, drama and yoga. He started a yogashala, a little school in the Jaganmohan Palace and handed over its administration to Krishnmacharya.

Under the king’s generous patronage, Krishnamacharya also authored what would be his magnum opus, the “Yoga Makaranda”, a two-volume encyclopedia on yoga in 1934. Whatever we know or have of modern day yoga practices is the result of Krishnamacharya’s hard work, meticulous study and teaching methodology.

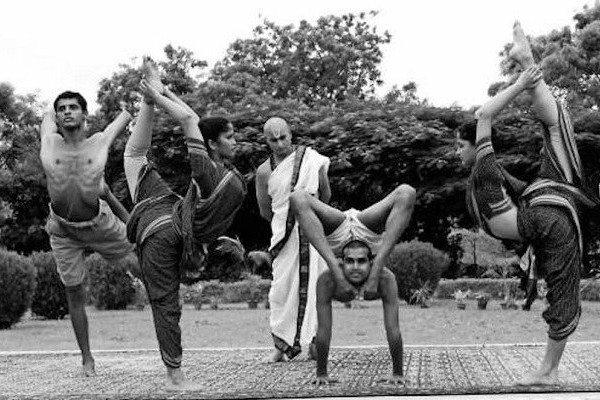

He had codified this ancient complicated science form and delivered it to the twentieth century as an art form worth loving. The Maharaja would flaunt Yoga demonstrations under the supervision of Krishnamacharya to visiting State guests.

Krishnamacharya was very progressive for his times. He encouraged girl child education and the training of girls in yoga and often conducted demonstrations with them. In addition to this Krishnamacharya was also teaching in the Sanskrit college. In 1938, the Maharaja even sponsored a film on Krishnamacharya. An extract of it is available on Youtube here:

All this glory ended in 1940, with the demise of the Maharaja. His successor did not have as much interest in yoga. When all the princely states joined the Indian union, the Raja of the time and new Chief Minister of Karnataka went a step further and shut the Yogashala.

A desperate Krishnamacharya now in his late fifties had to struggle to earn a livelihood to feed his family. He was offered a job of a lecturer in Vivekananda College in Madras. He migrated and lived there for the rest of his life. He lived to be 100 years old and passed away in 1989.

A staunch Shri Vaishnavite, he never crossed the country’s geographical boundaries. He trained some of the finest masters of modern yoga like BKS Iyengar and Pattabhi Jois.

Another student Indra Devi took Yoga to the west. They continued his legacy and teachings. But Krishnamacharya was a forgotten figure by the 21st century. No Padma awards or state recognitions came his way. Ideally, someone of his stature, scholarship and contribution deserved nothing less than the Bharat Ratna award. He was an authoritative reference point for anyone interested in studying yoga, classical music, Sanskrit grammar, Ayurveda, natural therapy, herbal medication, mathematics, philosophy or several other subjects.

Unfortunately the state failed to recognize this genius in his time. But with the annual Yoga Day celebration coming into vogue, the time may just be right to acknowledge Krishnamacharya’s contribution to modern Indian Yoga.

(Image courtesy – Krishnamurthy, Sudheer, Nagendra Prasad)

(Veejay Sai is an award-winning writer, editor and a culture critic. He writes extensively on Indian performing arts, cultural history, food and philosophy. He lives in New Delhi and can be reached at vs.veejaysai@gmail.com)

Source: Remembering Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, India’s first modern yoga guru | The News Minute