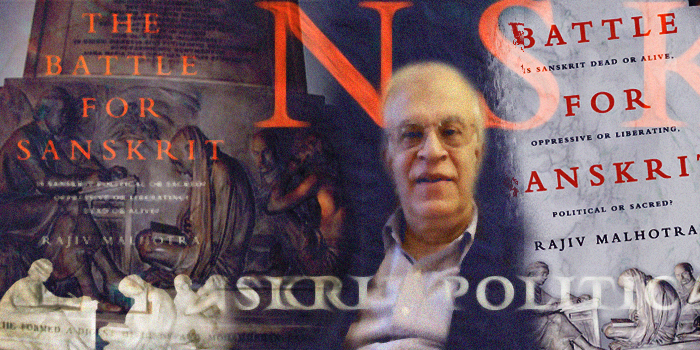

By Rajiv Malhotra

Those who are reading or about to read my new book, The Battle for Sanskrit, will be aware that I focus much of my attention on the prominent American Indologist Sheldon Pollock, who is the most high-profile and influential exponent of what I have called American Orientalism. I wish to explain why I have chosen him as my primary interlocutor and what my interactions with him have been. I wish to make as clear as possible the reasons for my engagement with him, and the experiences I have had in personal conversations with him and in reading his work.

I focus on Pollock (as opposed to taking a broad but superficial review of the work of multiple scholars) for the following reasons:

- To set a debate in motion against a powerful school of thought, one must dissect and respond to its very best minds and works, and not engage its weakest or most vulnerable scholars. This has also been the traditional Indian approach to debate since ancient times. Pollock deserves to be considered the foremost contemporary exponent of American Orientalism, as I will explain below.

- By naming Pollock as the leader, I invite him, his students and his collaborators to have open-minded conversations and debates with the goal of achieving a better mutual understanding. In effect, this book starts a sort of debate with the American Orientalist camp on their approach to Sanskrit and India studies.

- My focussed approach allows me to drill deep into the American Orientalist writings and offer my perspective. I can be concrete instead of making abstract generalizations.

- Pollock’s writings inform a whole generation of scholars as well as mainstream media personalities, and he has achieved unprecedented influence in compared to any other Western Indologist today.

- He has ‘gone native’ to a large extent and become assimilated in several Indian institutions, which dramatically increases his influence and power. Hence, we can speak of the Pollockization of Sanskrit studies.

This approach of debating the opposing side’s leader is consistent with my previous books. In each of them, I have addressed one big issue, an issue that was not in my view being addressed adequately by the adherents of the dharmic traditions; hence I tried to engage with its major exponents.

The entire enterprise of engagement and debate has been governed by my understanding of the Sanskrit tradition of purva-paksha. This practice makes huge demands on those who adopt it, demands that the opposing side must be seriously studied and directly engaged, and that differences not be suppressed but fully and publically aired and explored.

I have also been driven by a strong and growing conviction that traditional Hindu experts who are personally invested in Sanskrit culture and spiritual wisdom have until now failed to rise to the challenge of this engagement, for reasons I have explained in my writings.

Pollock is a worthy opponent, an Indologist and scholar of Sanskrit whose knowledge of the subject matter is unquestionably expert and dedicated. In choosing him as a focal point for my latest book, I have taken on the strongest possible representative and advocate for positions that I want to contest with mutual respect. Indeed, let me say at the outset that in order even to begin to meet the challenges of his work I have had both to immerse myself in his considerable body of scholarship and to pursue many of the sources on which he draws. I have had to read a vast body of secondary work by insiders and outsiders to the tradition alike in order to form my views. In the course of doing so, I have learned a great deal and gained a great measure of respect for him. I believe him to be a sincere lover of the subject he studies and I think his intentions are good, even when he may be blind to the bias caused by his own ideologies. My issue is that he sees the tradition too much through a reductionist western lens.

Pollock espouses views, takes positions and proffers analyses that should raise red flags for those who value the Vedic heritage of India and wish to see it flower as a resource for the future. Among other things, he is no friend of the Hindu religion – or of any religion, as far as I can see – and he routinely dismisses or discounts the kind of transcendental perspective that is precisely where its strength lies. Furthermore, he is overtly political in his allegiances and feels no compunction in taking positions and fostering interventions in the Indian context that are in line with his leftist and secular commitments, while at the same time taking funding from major capitalist elites. There is nothing wrong with this per se, and he is certainly entitled to his opinions, but he is often not transparent about the coloring of his lens by these ideological allegiances and sources of support. He seems blind to the way his politics affects his entire reading of the tradition, and does so, I believe, often in distorted and misleading ways.

I’d like my readers first fully to appreciate Pollock’s achievements and the importance of his role in Indology, so that they will better understand what I am trying to do and what I am up against in doing it. Let me now introduce Professor Pollock and his work for those who have not read him in detail.

Sheldon Pollock studied Latin and Greek classics at Harvard and this grounding has influenced his subsequent approach to philology in general Sanskrit in particular. After moving on to acquire his Ph.D in Sanskrit studies from Harvard under the famous Indologist, Daniel Ingalls, he spent the next few decades working diligently on a variety of Sanskrit texts. The resulting publications cover a vast canvas of topics in Sanskrit studies, one that has been rarely matched by Western scholars and even by many in India.

His first major study was on the Ramayana in the 1980s. In it, he consciously differentiated himself from fellow Western Indologists. He criticized scholars who romanticized the Sanskrit tradition, and argued for the use of a method he called ‘political philology’ to interpret Sanskrit texts. His approach was radically different from those of Ingalls and the major German Indologists in that he did not share their goal of representing the insider’s perspective on Sanskrit. In further work, he continued this trajectory, developing his critique of Sanskrit culture and tradition as encoding elitist values and oppressive constructs of women, dalits and Muslims. His career culminated in his magnum opus, The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India, a major work which needs to be read closely and in detail by anyone who wishes to engage with his positions.

Pollock has been widely recognized for his achievements both in the academy and beyond, in India as well as the US. Here are some of his accomplishments:

- He is a fellow of the prestigious American Academy of Arts and Sciences and is currently a chaired professor at Columbia University in Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies.

- The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India (2006) won the Coomaraswamy Prize from the Association of Asian Studies, as well as the Lionel Trilling Award.

- He has been awarded a Distinguished Achievement Award by the Mellon Foundation.

- At a 2008 conference entitled ‘Language, Culture and Power’ organized in his honour by his students, some of the most respected Indologists participated to pay him tribute.

- He was General Editor of the Clay Sanskrit Library, for which he also edited and translated a number of volumes.

- He has been joint editor of South Asia Across the Disciplines, a collaborative venture of the University of California Press, the University of Chicago Press and the Columbia University Press.

- He is currently the principal investigator of ‘SARIT: Enriching Digital Collections in Indology’, supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Bilateral Digital Humanities Program.

- One of his initiatives was the Ambedkar Sanskrit Fellowship Program at Columbia, which aims to establish an endowment to fund graduate studies in Sanskrit for dalit students.

- He directs the project ‘Sanskrit Knowledge Systems on the Eve of Colonialism’, in which scholars examine the state of knowledge that was produced in Sanskrit before colonialism.

- He is also editing a series of ‘Historical Sourcebooks in Classical Indian Thought’ while working on another book, titled Liberation Philology, for Harvard University Press.

These awards and recognitions have sealed his status in the eyes of most Indian intelligentsia as one of the few remaining scholars with the authority to interpret and speak about Sanskrit texts. Some examples of this recognition are listed below:

- The President of India awarded him the Certificate of Honour for Sanskrit, and subsequently the Padma Shri for his distinguished service in the field of letters.

- He has been featured as one of the star figures at the Jaipur Literary Festival over the past seven years, and is routinely invited to high-profile conclaves and seminars in India to help interpret India’s traditions for the Indian elite.

- He is interviewed by Tehelka news magazine and India’s NDTV network, and has received India Abroad’s Person of the Year award.

- He was the keynote speaker at the golden jubilee celebrations of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in Delhi.

- He serves as a juror on the committee that awards the Infosys Prize for Humanities and Social Sciences. One of the most prestigious feathers in his cap is his position as General Editor of the Murty Classical Library of India (Harvard University Press). I will examine this position in detail in a later chapter.

Pollock has many constituents and appeals to many disparate groups of people.

- The Indian left sees him as a priceless ally in exposing Hindu chauvinism by providing evidence of oppressiveness encoded within the Sanskrit tradition. For them, he is a worthy successor of D.D. Kosambi (the late Marxist scholar of Sanskrit) and far better equipped with updated Western social theories. They lionize him as a creator of new Marxist lineages even though, ironically, he is well-funded from capitalist pockets.

- Western academics see him as a unique scholar of intellectual history, his credentials bolstered by an access to Sanskrit that few of his peers possess. He is also a novel exponent in the application of Western social theories to Sanskrit-based cultures.

- Wealthy Indians see association with Pollock as opening doors for them to serve on boards of major institutions, giving them the proud sense of finally having arrived into the same league as the Rothschilds and the Rockefellers. Some of his benefactors might seek more mundane rewards, such as high-level networking.

- Indian Sanskrit scholars believe that Pollock’s elevated profile brings prestige to their field of study, which has otherwise been largely neglected by modern, sophisticated people. They perceive him as doing them a favour by serving as their ambassador; some hope that by professing loyalty to him, they might be lucky enough to secure foreign trips and funding for themselves.

- Traditional Hindu organizations are, in some cases, in awe of him, because his international affiliations give them a chance to bask in his reflected glory. By virtue of his presence, their tradition at least nominally secures a seat amongst the global elite. A good example of this phenomenon has been the desire of some administrators at Sringeri Sharada Peetham, established by Adi Shankara, to anoint him as a sort of ambassador for their legacy.

- The Indian government, media and public intellectuals tap superficially into his work as a source of one-liner wisdom – at least until recently. Pollock seems to provide an easy bandwagon, as it were, onto which they can jump without having to know much in the way of depth.

- Naïve Hindus feel proud that their heritage is being championed by an American from a prestigious university, and celebrate him for bringing their tradition into the limelight.

Pollock has offered a challenging critique of the tradition that deserves and needs close attention and engagement from the Indian traditional side. That engagement and critique have not so far been done. Though there are a few refutations of specific arguments in his work by western scholars, most of the general treatment of him is hagiographic, and the degree to which he has been lauded in India is based on superficial reading and media hype.

Sheldon Pollock is important for me to engage not only because of his giant reputation, but also because he represents the school of thought I have called the new American Orientalism. Not only does he rely on western literary and culture theory in his approach, he represents an assertively leftist and anti-spiritual approach to the subject. In this respect, he appears to be driven by a set of assumptions and historical experiences shaped by the trauma and guilt of native American genocide and slavery as well as by European philology.

Free from the obvious burdens of British colonialism, he engages in a subtler form of Orientalist imposition, the kind of imposition I have analyzed in my book Breaking India. This involves a tendentious reading of the Indian past and of its present problems that is fixated on caste, class, race and gender oppression and regards our cultural achievements as tainted by this legacy. I do not deny that these problems exist, and that they have ancient roots, as they do in the past of most global cultures today. But to read our entire tradition in these terms and to treat every attempt to revive and re-invigorate it as a form of nationalism or saffronization does no service either to our heritage or to our future.

My book looks at some key points of tension in Indology. It frames the issues by looking through the lenses of two opposing camps: the ‘insiders’ who subscribe to a Vedic worldview and the ‘outsiders’ who dismiss the spirituality of the Vedas. The byline of the book’s title captures three broad areas of contention that are discussed in its chapters:

Is Sanskrit political or sacred?

Oppressive or liberating?

Dead or alive?

In each pair of opposites, the first position mentioned is that of the outsiders, and the second position is that of the insiders. Thus, outsiders find Sanskrit and sanskriti to be political, oppressive and dead. The insiders would disagree and find our Sanskrit-based sanskriti to be sacred, liberating and alive.

Pollock’s critique is serious, informed, and motivated by strong commitments; but it is also myopic and captive to a single, reductionist political ideology. He deserves both respect for his positions and a reasoned response that is neither ignorant nor bombastic. Such a critique must acknowledge whatever in his work has validity, but also defend our tradition, its roots in a transcendental perspective and its capacity for growth and change. Such a response has been singularly lacking from the traditional side.

It is important to clarify that only a small portion of today’s Indologists are American Orientalists. It would be incorrect to project my critique of Orientalists onto the whole community of academic scholars of the social sciences and humanities, many of whom have gone to great lengths to shed the mentality I am criticizing here, and to understand and express an insider perspective, whether from the point of view of their own commitments and practices or as a matter of principle. However, the influence of Pollock’s group is significant in academics, media, education and public opinion. Hence, his works must be discussed in detail.